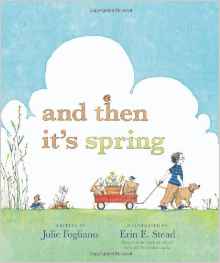

Erin was adamant that "images are my job." Her message for a picture book writer is to eliminate anything from your text that can be shown in a picture. For example, we don’t need to read about an object’s color or its size — the pictures will show us. Today's picture books are pared to the bone — 600 words or less — so every one of those words must contribute to the story or to the voice, and eliminating the visuals from the story is a way to cut your text. It also gives the artist free rein to add extra layers of interpretation to your story. For example, in AND THEN ITS SPRING by Julie Fogliano, illustrated by Erin Stead, Erin included animal characters: the animals aren't in the text but they add extra heart to the story.

Kids have a greater visual literacy than adults and spend more time looking at the illustrations. Kids notice things adults don’t (especially as the adult is usually focusing on the words), such as the number 5 on the side of the bus in A SICK DAY FOR AMOS MCGEE. (A child pointed out the tiny vole on one of the pages in HUNGRY COYOTE - I hadn’t noticed it.)

In her presentation, Erin talked about page turns and how they make the picture book art form what it is. To see what she means she suggested we type out the text of MY FRIEND RABBIT by Eric Rohmann: it doesn’t make sense until you compare it with the actual book and see the page turns. As the illustrator, Erin never relinquishes her control over the page turns. (And incidentally, using animals as main characters is one way not to exclude any group of kids from the story: all children can identify with animals.)

One of the great joys of creating picture books is seeing all the different ways that adults and kids interpret them. As a writer, I hope that my intent is clear but I want readers to react to my stories in different ways — life would be very boring if we were all the same. In Erin's words, " to want all books to work for all people in all situations" is "death to a book."

RSS Feed

RSS Feed