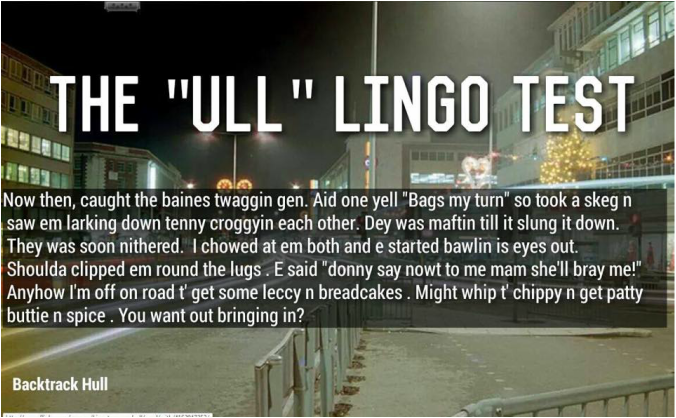

What most Americans don't understand is that within Great Britain there are countless local accents and dialects and most of them don't sound much like the Queen. Take a "shuftie" at the photo above and you'll see what I mean. It's an example (taken from the Backtrack Hull Facebook page) of the dialect from Hull in East Yorkshire, where I grew up .

Basically the text says that the narrator caught two kids taking an unauthorized day off school. The narrator heard one of them yell "It's my turn" and saw them playing in the tenfoot (an alley behind the houses) riding two-to-a-bike. They were hot until it began to pour with rain and then they got cold. The narrator says he/she should have clipped them round their ears, but instead he/she told them off and one started to cry, begging that the narrator not tell his/her mother because she would beat him. The narrator says he/she is going to pay for some electricity and buy some bread cakes. He/she might also go to the Fish and Chip shop to buy a patty sandwich (not sure if that's a meat patty or a potato patty) with chip spice. Did you get all that? Not exactly the Queen's English is it?

Words like "nithered" (cold), and "lugs" (ears), and "chowed" are so resonant of my childhood that I'm immediately transported to my junior school playground where I hear someone telling a friend she got chowed at by a teacher for doing something wrong and someone else describing a game in the tenfoot after school. LIZZIE AND THE STOLEN BABY, my upcoming middle-grade novel, is set in Yorkshire. Settings come to me early in my novel-writing process, in fact settings seem to spark many of my story ideas. Working to give enough rich setting details to show American children that they're not in Kansas any more, and certainly not in 2014, captivated me as I wrote this novel. But what to do about the dialog?

If you drive a couple of hours from Hull along the motorway to Sheffield, Leeds, or the Yorkshire Dales, you will hear completely different Yorkshire dialects. My novel is set in a fictional dale in the North York Moors (James Herriott country for those who love his books). I have characters who would have spoken with Hull accents, others with North Yorkshire accents, and others who would have used Romany words. In early drafts I incorporated a watered-down version of a standardized Yorkshire dialect, but a wise editor, Jill Davis at Katherine Tegen books, suggested I remove it. She felt that the dialog would pull the reader out of the story, causing the reader to stumble over unfamiliar words if the context around each word wasn't crystal clear. While I was sad to lose the wonderful Yorkshire words and phrases, I knew she was right. And besides, it wasn't really truly representative of the dialect spoken in the Dales because that would probably have been as incomprehensible as the sample above to most American readers (and probably most British ones too). In the end I mostly used standard Queen's English and a glossary to explain words such as "dale," "beck," and "conker."

Skilled writers get the setting details just right, transporting their readers into the story world without dumping paragraphs of information onto the page. I hope I've achieved that. 'Appen you'll buy my book for yer bonny bairns, take a gander and think it's a gradely read. If you do, I'll be right chuffed.

Oh - and here's a little more education for you taken from BBC North Yorkshire.

RSS Feed

RSS Feed